Before proceeding with Mary's story, I'll add a cautionary note ... she has been a troublemaker when it comes to my ability to uncover loads of definitive, accurate information about her life.

First of all ....

The period before 1837 is often referred to as the pre-Victorian era (as Queen Victoria ascended the throne mid-1837) and anyone attempting to trace their English ancestors during this period basically needs to rely on church registers.

Unfortunately these church records contain far less genealogical information than the civil records and were handwritten, making them quite hard to decipher most of the time.

Second of all ...

I've found that the surname Ayears appears to have different variations, spelt in a few different ways including 'Ayers' and 'Airs'. This has led to a long, long road of assumption and guessing when it comes to records relating to my 4x great grandmother! I've spent many, many, many months trying to cross-reference with family trees on Ancestry.com and as many records as I could find on several sites such as Family Search and Find My Past. It's been a messy and confusing journey.

Thirdly ...

I've found that researching female ancestors going back two generations and more is always a little troublesome. The details of their lives are rarely captured in the records that are available, unless you're fortunate enough to have treasures such as diaries or family stories passed down. All I've managed to uncover are a few facts from a couple of very short periods of time - between 1797 and 1808, and then between 1851 and 1858. So here's what I think I know about parts of Mary's story!

When Mary Ayears was born around 1770, her father Samuel Ayears was around 20 years of age, and her mother Mary Vicary was about the same age.

My research led me to a baptism record showing a Mary Airs was baptised at the Church of Saint Mary Major in Exeter, Devon, England in August of 1770.

I don't have an exact date of birth for this Mary, and I admit I followed information from family trees on Ancestry.com to track down this record.

Whether or not it's really my 4x great grandmother is probably debatable, but other information leads me to believe it's quite likely.

Later records, which are definitely more reliable, indicate that Mary was likely born around 1768, so that places the Mary Airs from this baptism record at approximately the right time. Records of Mary's marriage later on and the baptism records for her children show that all these events happened in Exeter, so again I think it's highly likely that Mary herself was born and baptised in that same town.

Around 1770, Exeter was a economically powerful city with a very strong trade of wool. The reigning monarch at this time was King George 111, and it was in August of 1770 that Captain James Cook claimed the entire east coast of New Holland for Great Britain. It was of course later to become Australia, and the home for descendants of one of Mary's daughters Anne (known as Nancy) my 3x great grandmother, and for descendants of her grandson Joseph Hutton.

Apart from a possible birth year, baptism date, baptism place, and parent names, I have no information at all about Mary's childhood. The next fact I do know, and am sure about, is that Mary Airs/Ayears married John Littlejohns in December of 1797 when she was around 27-29 years old. On the marriage record, Mary's maiden name was spelt as 'Ayears'.

Around 1770, Exeter was a economically powerful city with a very strong trade of wool. The reigning monarch at this time was King George 111, and it was in August of 1770 that Captain James Cook claimed the entire east coast of New Holland for Great Britain. It was of course later to become Australia, and the home for descendants of one of Mary's daughters Anne (known as Nancy) my 3x great grandmother, and for descendants of her grandson Joseph Hutton.

Apart from a possible birth year, baptism date, baptism place, and parent names, I have no information at all about Mary's childhood. The next fact I do know, and am sure about, is that Mary Airs/Ayears married John Littlejohns in December of 1797 when she was around 27-29 years old. On the marriage record, Mary's maiden name was spelt as 'Ayears'.

According to information sourced from other descendants' family research, Mary and John already had three children before they married.

Well, the assumption is that these are John's children as well as they were given the surname of Littlejohns.

Son Henry was born in 1794, but sadly died when he was less than a year old.

Daughter Frances, known as Fanny, was born in 1795.

Daughter Mary Ann was born in April of 1797.

Interestingly, Mary's father, Samuel Ayears, died on the 14th of December 1797; and Mary married on the 19th of December.

Son Henry was born in 1794, but sadly died when he was less than a year old.

Daughter Frances, known as Fanny, was born in 1795.

Daughter Mary Ann was born in April of 1797.

Interestingly, Mary's father, Samuel Ayears, died on the 14th of December 1797; and Mary married on the 19th of December.

I could make all sorts of assumptions about this fact, one of which would be that Mary had been living out-of-wedlock with John for a number of years likely as a result of her father's objection to the match. Mary was however old enough to marry without her father's consent, so I'm not sure that would be an accurate assumption. Anyway, very shortly after father's death, Mary seems to have married the father of her children.

After the marriage of Mary and John in December that year, the family grew.

Jane was born mid-1800, but unfortunately passed away in September.

Anne, known as Nancy, Littlejohns (my 3x great grandmother) came along in November of 1801, when Mary was aged around 31-33.

John was born in May of 1803, but he died in February the following year.

John Edwin was born in 1807. Mary was now around 37-39 years old.

By the year 1808, out of the seven children that Mary gave birth to, there were three daughters and one son who had survived their infancy.

After the marriage of Mary and John in December that year, the family grew.

Jane was born mid-1800, but unfortunately passed away in September.

Anne, known as Nancy, Littlejohns (my 3x great grandmother) came along in November of 1801, when Mary was aged around 31-33.

John was born in May of 1803, but he died in February the following year.

John Edwin was born in 1807. Mary was now around 37-39 years old.

By the year 1808, out of the seven children that Mary gave birth to, there were three daughters and one son who had survived their infancy.

It's very difficult to glean information about Mary's adult life around the time of and after the birth of her children, but clues from records later on point to the fact that it's likely Mary, her husband John and their family of four, had a hard life and were probably amongst the poorer class in Exeter society.

John worked as a 'fuller', often referred to as a 'tucker', which was not a well-paying job and the conditions of employment were very tough. A fuller (tucker) worked long hours every day. It was their job to clean wool cloth during the cloth making process to eliminate dirt and oil, and make it thicker. Before the cloth got to the fullers (tuckers) it was soaked in urine! John's job would have been back-breaking and extremely unpleasant.

John worked as a 'fuller', often referred to as a 'tucker', which was not a well-paying job and the conditions of employment were very tough. A fuller (tucker) worked long hours every day. It was their job to clean wool cloth during the cloth making process to eliminate dirt and oil, and make it thicker. Before the cloth got to the fullers (tuckers) it was soaked in urine! John's job would have been back-breaking and extremely unpleasant.

I imagine Mary worked in some lowly, poorly paid job in the mills of Exeter as well, but I have not yet found any proof of that, and likely never will. Records of women's working life from that era are rare.

Mary and John were married for about 44 years until John died sometime around 1841. Mary was aged around 71-73 at that time.

By then, Mary's eldest daughter Fanny was a widow as well. She had married Joseph Perkiss Hutton, and had given birth to three children, but only two had survived into adulthood. Fanny's son Joseph, Mary's grandson, had been transported to the colonies ten years earlier at the young age of 17. He had in fact been sentenced to death, but his conviction had been commuted to transportation for a period of 14 years. In reality, transportation to Australia really was a life sentence. He lived out the rest of his life in Australia and probably had very little contact with either his mother or his grandmother Mary.

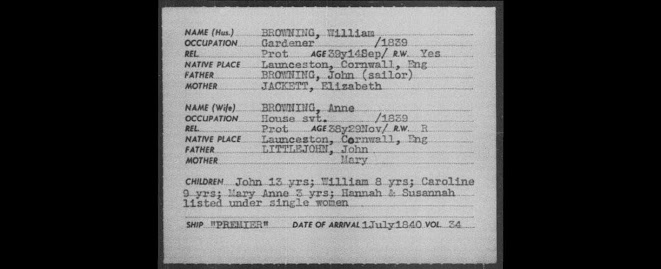

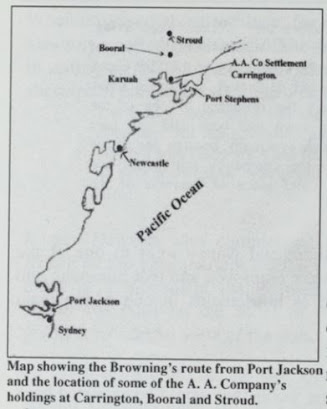

Mary's youngest daughter Anne (known as Nancy) had married William Henry Browning almost twenty years before, in the same church as Mary and John. By 1841 though, Anne was in Australia, having migrated with her husband and six children. She lived the rest of her life in the colonies, far away from her mother.

By 1851, ten years after the death of her husband, Mary was living in the Almshouses in Exeter, with another daughter Mary Anne Harris (nee Ayears).

Mary and John were married for about 44 years until John died sometime around 1841. Mary was aged around 71-73 at that time.

By then, Mary's eldest daughter Fanny was a widow as well. She had married Joseph Perkiss Hutton, and had given birth to three children, but only two had survived into adulthood. Fanny's son Joseph, Mary's grandson, had been transported to the colonies ten years earlier at the young age of 17. He had in fact been sentenced to death, but his conviction had been commuted to transportation for a period of 14 years. In reality, transportation to Australia really was a life sentence. He lived out the rest of his life in Australia and probably had very little contact with either his mother or his grandmother Mary.

Mary's youngest daughter Anne (known as Nancy) had married William Henry Browning almost twenty years before, in the same church as Mary and John. By 1841 though, Anne was in Australia, having migrated with her husband and six children. She lived the rest of her life in the colonies, far away from her mother.

By 1851, ten years after the death of her husband, Mary was living in the Almshouses in Exeter, with another daughter Mary Anne Harris (nee Ayears).

|

| 1851 Census - St David's, Exeter, Devon, England |

Mary was recorded as being an "Almsperson / Tucker's Widow". Almsperson basically meant "one who is dependent on the receipt of alms", a "a pauper". The census record indicates she was now aged 83. She was living in the Atwills Almshouses on New North Road in Exeter, with her daughter Mary Anne who was listed as an "Upholstress". It seems that daughter Mary Anne's husband had died by this time, as she was now living with her mother.

An excerpt from the book 'A Topographical Dictionary of England' published in 1833 states:

"Atwill's almshouses were founded and endowed by the corporation, with the arrears of Mr. Atwill's charity in 1717, for fifteen aged woollen manufacturers, appointed by the corporation: the annual income of this charity amounts to about £320."

Almshouses were generally houses or property left to a parish by a community-minded benefactor who was acting philanthropically, and were outside government control. People who were accepted into these almshouses were approved in some way. They would no have been vagrants or outcasts, but were likely to have been regarded as respectable and part of a network of obligation which ensure their admission.

In Mary's case, she was the widow of a 'tucker', another name for a fuller, and the Atwill's Almshouses were by that time earmarked for "poor and aged" woollen trade workers as mentioned in the excerpt from information on the website Genuki: Almshouses, Devon, Exeter, 1850:

ATWILL'S ALMSHOUSES, in New North road, are neat stone dwellings on an elevated site. In 1588, Lawrence Atwill left about 320 acres of land, and several houses, &c., in the parishes of St. Thomas, Whitstone, and Uffculme, to the Corporation of Exeter, upon trust to apply the yearly profits thereof in setting the poor to work. As the charitable intentions of the testator could not be strictly or beneficially carried into effect, a new scheme was sanctioned by the Court of Chancery in 1771, directing that in future the rents and profits of the charity estate should be applied in the erection and support of almshouses for the reception of poor aged woollen weavers, &c., of the city, who should be provided with looms, &c., and small weekly stipends. Accordingly, 12 almshouses were built in 1772. In consequence of the increased income of the charity, these almshouses were enlarged in 1815, at the cost of £425; and again in 1839, at the cost of £160. They are now occupied by 24 almspeople, who are provided with coals in winter; but only 16 of them have weekly stipends of 2s. 6d. each, and none of them are provided with looms. The charity estate is let to fifteen tenants, at rents amounting to about £250 per annum, and large sums are occasionally received for the renewal of leases and the sale of timber.

I believe that Mary and her daughter Mary Anne were two of the 24 almspeople mentioned as living in the Atwill's Almshoues in 1850, and it's likely neither of them were receiving the weekly stipend. It's more likely that Mary was relying on the income of her daughter to provide food and other essentials. On a positive note though, at least they had a home, more or less guaranteed, and were provided with coal in winter!

There were 24 houses (more akin to flats) in 3 blocks that were designed in a gabled Tudor style.

The 'houses' were likely to have consisted of one or two rooms with a fireplace. It would have provided Mary and her daughter with a private space so they would have been able to live quite independently, despite their economic dependence.

Mary died at the Almshouses in April of 1858 at the age of 90, as indicated on her death certificate. The cause of death was listed as "natural decay", so it sounds as though she was not ailing in any way or suffering at the end of her long tough life.

She was buried five days later in the Parish of St. David and her death notice, albeit brief, does describe her as "greatly respected by all who knew her".

Mary was survived by her three daughters, Frances Hutton nee Littlejohns, Mary Anne Harris nee Littlejohns, Anne (known as Nancy) Browning nee Littlejohns; and her son John Edwin Littlejohns.