When James was born in July of 1792, his father John Hukins was 33 years old and his mother, Elizabeth Crittenden was 38. James was the seventh child and the second son born to John and Elizabeth, according to the records I've managed to track down so far.

His eldest sister Sarah had been born in 1777.

Brother Richard came along in 1779.

Sister Mary had been born in 1781.

Sister Elizabeth had come along in 1782.

Sister Charlotte had been born in 1785.

Sister Ann came along in 1788.

It does seem a little odd that John and Elizabeth had not named a son after his father, given they had named one of their daughters after her mother. Perhaps there had been another little one born at some stage, but had died quite soon afterwards and had been named John. I have not found a record to back up this assumption though.

James, 3x great grandfather, was born in Woodchurch, Kent, England where the Hukins family had been farming the land for two generations up to that point.

|

| Map showing the location of the Susan's Hill area |

James' great grandfather, John Hukins (c. 1701-1763) had first come to Woodchurch around 1730 and farmed at 'Susan's Hill', on the outskirts of the village of Woodchurch. That was the beginning of the history of the Hukins family in this area.

|

| Map showing the location of Hukins Farm on the outskirts of Woodchurch |

My 3x great grandfather James would have grown up on the land farmed by his father, John Hukins (1759-1819).

This is still known as 'Hukins Farm' and is located on Redbrook Street, half a mile north of Susan's Hill, and overlooking the land farmed by his great grandfather.

(This information is sourced from an article titled 'James & Susannah Hukins', written by Josie Mackie in the book named 'Leaving Woodchurch - Emigration from Woodchurch since the Seventeenth Century'. I'm fortunate enough to have copy of this book and it has been invaluable for my research on James. It has certainly made the job of digging up my 3x great grandfather's past a little easier).

The house that still stands on Hukins Farm is likely to be the house where my 3x great grandfather spent his childhood.

James obviously had a great love for the place where he grew up and was to pay respect to his childhood home later in his life, as will be mentioned a little further on in this post.

Sadly, when James was aged 16 his mother Elizabeth passed away. James' father was now a widow but James' siblings were aged between 20 and 31 so it's likely most of them were helping out on the farm, or had begun lives of their own. James remained living with his father for a number of years after the death of his mother.

At the age of 22, my 3x great grandfather James married Susannah Fullagar.

Banns were posted in December of 1814 and early January of 1815,

They were married in the All Saint's Church in Woodchurch on the 12th of January 1815.

This is still known as 'Hukins Farm' and is located on Redbrook Street, half a mile north of Susan's Hill, and overlooking the land farmed by his great grandfather.

(This information is sourced from an article titled 'James & Susannah Hukins', written by Josie Mackie in the book named 'Leaving Woodchurch - Emigration from Woodchurch since the Seventeenth Century'. I'm fortunate enough to have copy of this book and it has been invaluable for my research on James. It has certainly made the job of digging up my 3x great grandfather's past a little easier).

|

| The farmhouse on Hukins Farm |

The house that still stands on Hukins Farm is likely to be the house where my 3x great grandfather spent his childhood.

James obviously had a great love for the place where he grew up and was to pay respect to his childhood home later in his life, as will be mentioned a little further on in this post.

Sadly, when James was aged 16 his mother Elizabeth passed away. James' father was now a widow but James' siblings were aged between 20 and 31 so it's likely most of them were helping out on the farm, or had begun lives of their own. James remained living with his father for a number of years after the death of his mother.

At the age of 22, my 3x great grandfather James married Susannah Fullagar.

They were married in the All Saint's Church in Woodchurch on the 12th of January 1815.

The two families, the Hukins and the Fullagars, had been friends for three generations.

Susannah was the great granddaughter of John Fullagar (1700-1746) who had settled in Woodchurch in 1734 and ran the Bonny Cravat Inn till his death 12 years later. Susannah's father, John Fullagar, had also run the Bonny Cravat for 20 years. Susannah's mother Elizabeth took over after the death of her husband John. Susannah's brother Thomas had then taken over from his mother and ran the inn for 4 years.

James (my 3x great grandfather) was the grandson of John Hukins (1730-1803) who had run the Bonny Cravat Inn for seventeen years. James' Great Uncle (his grandfather's brother) James Hukins (1741-1823) had taken over as innkeeper in 1775 as well.

The running of the Bonny Cravat Inn had basically been passed between Fullagars and Hukins for nearly a century between 1734 and 1820.

As mentioned previously, my 3x great grandfather James continued working as a farm labourer on his father's farm until he started his own working life as Innkeeper at the Bonny Cravat in 1824. He took over the license along with his wife Susannah, and they ran the inn for 13 years. Inn-keeping was in their blood!

During the time that James was innkeeper, the Bonny Cravat Inn was often used as a courtroom and several smugglers were sentenced to death inside the inn before being hung on gallows that were erected outside!

After James married Susannah, they went on to have nine children over a period of sixteen years.

Daughter Elizabeth (known as Betsy) was born only seven months after James and Susannah had married, in July of 1815.

Son John was born in 1817.

James' father, John Hukins, died two years later in 1819. James was now aged 27.

Son James was born in 1820.

Son Crittenden came along in 1821.

Son Adolphus was born in 1823.

It was during the following year that my 3x great grandfather began his career as an innkeeper.

Daughter Sabina was born at the beginning of 1825.

Sadly, James lost his sister Elizabeth at the end of 1825. She was survived by her husband and four children.

In 1828, son Norman was born, but sadly only survived for a couple of weeks.

Daughter Cassandra was born in 1829.

Daughter Adelaide came along in 1832. By this time James was 39 years old.

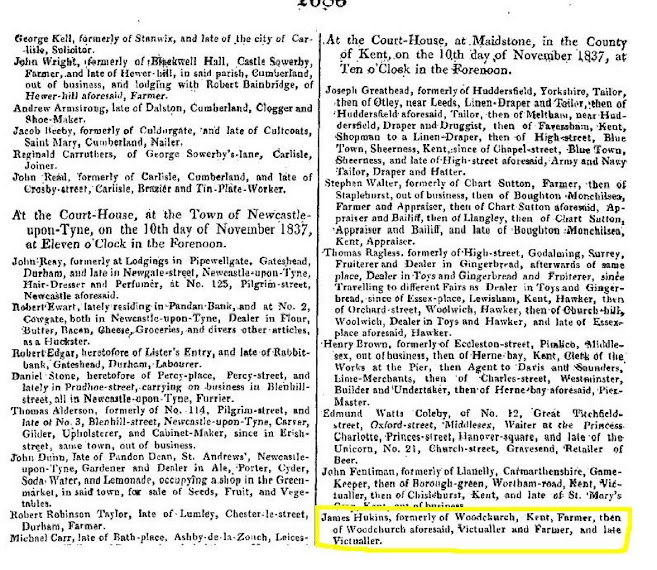

James and wife Susannah were still innkeepers at this time, but this was not to last. By 1837 James had found himself in dire circumstances. He was by now in severe financial trouble, evidenced in the listing that appeared in the London Gazette of late 1837.

James was petitioning the Court for Relief of Insolvent Debtors. Interestingly, the article lists James as "formerly of Woodchurch", so it seems he had left the village, had given up running the inn, and appeared to be living in Maidstone, Kent at this time.

He must have moved back to Woodchurch though because a mere two years later James and his family were preparing to emigrate, and were being assisted by Parish funds.

Minutes of the Woodchurch Parish meeting of the 30th of March 1839 lists items provided by the parish to assist the Hukins family for emigration to Australia aboard the ship Cornwall.

The minutes show that James Hukins was provided with:

"2 pairs duck trousers, 1 smock frock, 8 shirts, 2 flannel jackets, 1 flannel drawers, 1 cotton drawers stout, 5 pairs woollen hose, 1 hat, 2 pair shirts."

Given that James was provided with a "stout" pair of cotton drawers, I think it's safe to assume that he was a large man!

As for 'duck trousers', I had to look that one up!

Apparently it refers to trousers made of cotton duck material - heavy, plain woven cotton fabric and would have looked something like this:

James, aged 47, his wife Susannah, aged 48, their seven unmarried children, John aged 22, James aged 19, Crittenden aged 18, Adolphus (my great great grandfather) aged 16, Sabina aged 13, Cassandra aged 10 and Adelaide aged 7 all travelled to Gravesend to board the ship that would take them to Australia.

Susannah was the great granddaughter of John Fullagar (1700-1746) who had settled in Woodchurch in 1734 and ran the Bonny Cravat Inn till his death 12 years later. Susannah's father, John Fullagar, had also run the Bonny Cravat for 20 years. Susannah's mother Elizabeth took over after the death of her husband John. Susannah's brother Thomas had then taken over from his mother and ran the inn for 4 years.

James (my 3x great grandfather) was the grandson of John Hukins (1730-1803) who had run the Bonny Cravat Inn for seventeen years. James' Great Uncle (his grandfather's brother) James Hukins (1741-1823) had taken over as innkeeper in 1775 as well.

The running of the Bonny Cravat Inn had basically been passed between Fullagars and Hukins for nearly a century between 1734 and 1820.

As mentioned previously, my 3x great grandfather James continued working as a farm labourer on his father's farm until he started his own working life as Innkeeper at the Bonny Cravat in 1824. He took over the license along with his wife Susannah, and they ran the inn for 13 years. Inn-keeping was in their blood!

During the time that James was innkeeper, the Bonny Cravat Inn was often used as a courtroom and several smugglers were sentenced to death inside the inn before being hung on gallows that were erected outside!

After James married Susannah, they went on to have nine children over a period of sixteen years.

Daughter Elizabeth (known as Betsy) was born only seven months after James and Susannah had married, in July of 1815.

Son John was born in 1817.

James' father, John Hukins, died two years later in 1819. James was now aged 27.

Son James was born in 1820.

Son Crittenden came along in 1821.

Son Adolphus was born in 1823.

It was during the following year that my 3x great grandfather began his career as an innkeeper.

Daughter Sabina was born at the beginning of 1825.

Sadly, James lost his sister Elizabeth at the end of 1825. She was survived by her husband and four children.

In 1828, son Norman was born, but sadly only survived for a couple of weeks.

Daughter Cassandra was born in 1829.

Daughter Adelaide came along in 1832. By this time James was 39 years old.

James and wife Susannah were still innkeepers at this time, but this was not to last. By 1837 James had found himself in dire circumstances. He was by now in severe financial trouble, evidenced in the listing that appeared in the London Gazette of late 1837.

|

| London Gazette Nov 1837 |

He must have moved back to Woodchurch though because a mere two years later James and his family were preparing to emigrate, and were being assisted by Parish funds.

Minutes of the Woodchurch Parish meeting of the 30th of March 1839 lists items provided by the parish to assist the Hukins family for emigration to Australia aboard the ship Cornwall.

The minutes show that James Hukins was provided with:

"2 pairs duck trousers, 1 smock frock, 8 shirts, 2 flannel jackets, 1 flannel drawers, 1 cotton drawers stout, 5 pairs woollen hose, 1 hat, 2 pair shirts."

Given that James was provided with a "stout" pair of cotton drawers, I think it's safe to assume that he was a large man!

As for 'duck trousers', I had to look that one up!

Apparently it refers to trousers made of cotton duck material - heavy, plain woven cotton fabric and would have looked something like this:

|

| Gravesend, on the River Thames, was the major port of departure for emigrants |

James, aged 47, his wife Susannah, aged 48, their seven unmarried children, John aged 22, James aged 19, Crittenden aged 18, Adolphus (my great great grandfather) aged 16, Sabina aged 13, Cassandra aged 10 and Adelaide aged 7 all travelled to Gravesend to board the ship that would take them to Australia.

Accompanying them was their married daughter, Elizabeth aged 24, her husband Edward Daw and young son Edward, aged 1; as well as Elizabeth's brother-in-law Philp Daw, his wife Sarah and their four children.

James, his wife Susannah and their four youngest children were listed together as a family on the immigrant passenger record, whilst the three older boys were listed under 'unmarried males' and their eldest daughter was listed with her husband and child as a separate family.

The ship Cornwall departed Gravesend on the 12th of May 1839 and arrived in Sydney, Australia on the 1st of September 1839. The voyage lasted for 114 days and covered 15, 682 miles. In anyone's mind's eye this sounds like a challenging experience, especially given the time period.

At no point during the long journey were the emigrants able to disembark and stretch their legs. They would have seen the Isle of Wight three days into the voyage, then on day 71 the ship have passed the Cape of Good Hope, after which it would have entered the Indian Ocean. After a further 16 days and 2,650 miles, the ship would have arrived at Ile St. Paul, midway between the Cape of Good Hope and the west coast of Australia. The Cornwall 'hove to' for the day near this uninhabited volcanic island, and the opportunity was taken to catch and eat fresh fish.

On day 107 of the journey, the emigrants first sighted their new home when their ship entered Bass Strait, between the southern coast of mainland Australia and the island of Van Diemen's Land (as it was known then). Three days later, Cornwall rounded Cape Howe, where the coast of New South Wales began; then on day 114 at 2 a.m. the light on South Head was seen and the Cornwall 'hove to' until daylight. At 6.30 a.m. on September 2nd, with the pilot aboard, the ship passed through Sydney Heads and entered Port Jackson. The emigrants were allowed to disembark the following day, September 3rd, after several gentlemen boarded the ship to inspect the emigrants and select servants for their estates.

I have spoken in previous posts about the journeys of many of my immigrant ancestors and have covered things like - the sights seen on the journey, the living conditions experienced, the length of the voyages and some of the more significant events along the way. The reason I've been able to find out this type of information is that the colonial government required that each immigrant ship sail with a medical officer (after the disastrous voyage of the Second Fleet in 1789 - known afterwards as the Death Fleet - arriving in New South Wales with a mortality rate of 40%), and these men often kept quite detailed records.

Dr. Gilbert King was appointed Surgeon Superintendent on the immigrant ship Cornwall from London to Sydney in 1839, and his report gives a few extra details about the journey undertaken by 3x great grandfather and his family.

After arriving in Sydney, my 3x great grandfather James found work as a farm labourer with a Thomas Croft Esq. at Wollongong, about 50 miles to the south of Sydney. My 3x great grandmother, James' wife Susannah was also employed as a farm labourer, and all the younger children would have worked alongside their parents.

The three older sons found work in Sydney and remained there. The eldest son John and second eldest James both found work with Bishop Broughton (the first Anglican bishop in Australia) as a gardener and coachman, respectively. The third eldest son, Crittenden, found work with a Mr. Foster as a groom.

Tragedy struck the family almost immediately after their arrival however. Within four months, Crittenden was killed in an accident with horses. He died in January of 1840 at the age of 18. That would have been a terrible blow for James, having already lost a son about eleven years earlier.

By mid-1840 James had attained the position of convict overseer on the Berry Estate. At that time was estate around 32,000 acres in size held by Alexander Berry, located north of the Shoalhaven River. Over time though the Berry Estate was enlarged by grant and purchase to 80,000 acres in size, stretching from Gerringong in the north to Wollumboola in the south, and from the coast to beyond Broughton Creek (later re-named Berry) in the west.

This was a position of some standing and importance. It does seem however, that James had empathy towards the convicts. A tale shared by his 3x great granddaughter and recorded in the book 'Leaving Woodchurch - Emigration from Woodchurch since the Seventeenth Century' states that:

In recognition of his services as a convict overseer, James was offered a grant of land some miles south of Wollongong, but he declined this offer as he considered the land impoverished and not worthy of his time and labour!

James worked as a tenant farmer for landowners such as Captain Steven Addison Esq., who had a property of considerable size known as the Peterborough Estate in the Shellharbour area.

As a matter of fact, Steven Addison made particular mention of my 3x great grandfather during his speech at his farewell dinner held in 1848.

Part of this speech was published in an article in the Sydney Morning Herald as follows:

"Captain Addison rose to return thanks ... he had come to this district and had settled on what all thought a wilderness. He had greatly improved it ... but if he had not been blessed with such tenants as Mr. James Hukins and family, and ably supported by good neighbours, all he could have done would have availed to nothing."

The life of a tenant farmer would have been one of daily toil from sun-up to sunset.

Landowners would let out plots of land and grant "clearing leases". The tenant farmer was required to clear trees, fence plots and erect habitable structures within the period of the lease, which was usually two to five years.

Plots of land for clearing leases were mostly around ten or twelve acres, but if a tenant farmer was industrious and could prove his worth, he might be allowed as many acres as he could manage. If a tenant farmer had strong hard-working family members to help, then a clearing lease might be granted for plots as large as twenty or thirty acres.

Once cleared, the land was "let" on the halves principle - the landowner provided the land, seed, animals and tools and then took half the produce as a form of rent payment. This was the life of James Hukins for around ten years, beginning when we would have been around 52 years of age.

In 1854, at the ripe old age of 62, James then became a landowner himself. He bought 464 acres of land on Curramore Estate in Jamberoo. A year after that he sold 114 of these acres to each of his three sons - John, James and Adolphus - and kept 114 acres for himself. He named this patch of land 'Susan's Hill' which you may recall had been the name of a tract of land back in Devon, England where he had spent his childhood years.

James was to live out the remainder of his life at 'Susan's Hill'.

Sadly, in 1861 two of his sisters died, and then in 1862 his wife, Susannah, passed away. They had been married for 47 years and James was 69 years of age.

James himself passed away in 1871, at the age of 79.

James, his wife Susannah and their four youngest children were listed together as a family on the immigrant passenger record, whilst the three older boys were listed under 'unmarried males' and their eldest daughter was listed with her husband and child as a separate family.

The ship Cornwall departed Gravesend on the 12th of May 1839 and arrived in Sydney, Australia on the 1st of September 1839. The voyage lasted for 114 days and covered 15, 682 miles. In anyone's mind's eye this sounds like a challenging experience, especially given the time period.

At no point during the long journey were the emigrants able to disembark and stretch their legs. They would have seen the Isle of Wight three days into the voyage, then on day 71 the ship have passed the Cape of Good Hope, after which it would have entered the Indian Ocean. After a further 16 days and 2,650 miles, the ship would have arrived at Ile St. Paul, midway between the Cape of Good Hope and the west coast of Australia. The Cornwall 'hove to' for the day near this uninhabited volcanic island, and the opportunity was taken to catch and eat fresh fish.

On day 107 of the journey, the emigrants first sighted their new home when their ship entered Bass Strait, between the southern coast of mainland Australia and the island of Van Diemen's Land (as it was known then). Three days later, Cornwall rounded Cape Howe, where the coast of New South Wales began; then on day 114 at 2 a.m. the light on South Head was seen and the Cornwall 'hove to' until daylight. At 6.30 a.m. on September 2nd, with the pilot aboard, the ship passed through Sydney Heads and entered Port Jackson. The emigrants were allowed to disembark the following day, September 3rd, after several gentlemen boarded the ship to inspect the emigrants and select servants for their estates.

I have spoken in previous posts about the journeys of many of my immigrant ancestors and have covered things like - the sights seen on the journey, the living conditions experienced, the length of the voyages and some of the more significant events along the way. The reason I've been able to find out this type of information is that the colonial government required that each immigrant ship sail with a medical officer (after the disastrous voyage of the Second Fleet in 1789 - known afterwards as the Death Fleet - arriving in New South Wales with a mortality rate of 40%), and these men often kept quite detailed records.

Dr. Gilbert King was appointed Surgeon Superintendent on the immigrant ship Cornwall from London to Sydney in 1839, and his report gives a few extra details about the journey undertaken by 3x great grandfather and his family.

"When the weather permitted Divine Service was performed by reading the Prayers and a sermon afterwards every Sunday performed on the quarter deck, but if unfavourable that important duty was performed between decks, to the emigrants. In the afternoon, and every evening during the voyage we had a short religious service on the main deck. ---- A school was established shortly after we sailed, and from forty to sixty children attended with decided benefit. The regulations established for the preservation of health under cleanliness and ventilation. The beds were stowed on deck every morning unless the weather was very boisterous and wet. The emigrants washed themselves every morning, and having appointed two washing days weekly, every facility was thus afforded them of keeping their linen clean. Once a week their beds were opened out and aired on deck. ---- The greater part of the day was occupied performing the service connected with the above arrangements and in attending to their own personal and family caring; and in fine weather they had singing and dancing on the quarter deck every lawful day.Signed, Gilbert King M D Surgeon."

After arriving in Sydney, my 3x great grandfather James found work as a farm labourer with a Thomas Croft Esq. at Wollongong, about 50 miles to the south of Sydney. My 3x great grandmother, James' wife Susannah was also employed as a farm labourer, and all the younger children would have worked alongside their parents.

The three older sons found work in Sydney and remained there. The eldest son John and second eldest James both found work with Bishop Broughton (the first Anglican bishop in Australia) as a gardener and coachman, respectively. The third eldest son, Crittenden, found work with a Mr. Foster as a groom.

Tragedy struck the family almost immediately after their arrival however. Within four months, Crittenden was killed in an accident with horses. He died in January of 1840 at the age of 18. That would have been a terrible blow for James, having already lost a son about eleven years earlier.

By mid-1840 James had attained the position of convict overseer on the Berry Estate. At that time was estate around 32,000 acres in size held by Alexander Berry, located north of the Shoalhaven River. Over time though the Berry Estate was enlarged by grant and purchase to 80,000 acres in size, stretching from Gerringong in the north to Wollumboola in the south, and from the coast to beyond Broughton Creek (later re-named Berry) in the west.

This was a position of some standing and importance. It does seem however, that James had empathy towards the convicts. A tale shared by his 3x great granddaughter and recorded in the book 'Leaving Woodchurch - Emigration from Woodchurch since the Seventeenth Century' states that:

"James' convict master realised that his sugar, which was a valuable and scarce resource at that time, was going missing. He told James that he believed the convicts in James' charge were responsible, a thing which James denied absolutely.

A trap was set to prove this one or another and who should fall into that trap but the sister-in-law of the convict master himself, who wanted the sugar for her cooking!

It may well be that James had some sympathy for the convicts under his charge as he would have known at least one who was transported for seven years, William Hampton, brother of Benjamin Hampton, one of his fellow travellers on the Cornwall."

In recognition of his services as a convict overseer, James was offered a grant of land some miles south of Wollongong, but he declined this offer as he considered the land impoverished and not worthy of his time and labour!

James worked as a tenant farmer for landowners such as Captain Steven Addison Esq., who had a property of considerable size known as the Peterborough Estate in the Shellharbour area.

As a matter of fact, Steven Addison made particular mention of my 3x great grandfather during his speech at his farewell dinner held in 1848.

Part of this speech was published in an article in the Sydney Morning Herald as follows:

|

| Sydney Morning Herald - Wed 20 Sept 1848 p2 |

"Captain Addison rose to return thanks ... he had come to this district and had settled on what all thought a wilderness. He had greatly improved it ... but if he had not been blessed with such tenants as Mr. James Hukins and family, and ably supported by good neighbours, all he could have done would have availed to nothing."

The life of a tenant farmer would have been one of daily toil from sun-up to sunset.

Landowners would let out plots of land and grant "clearing leases". The tenant farmer was required to clear trees, fence plots and erect habitable structures within the period of the lease, which was usually two to five years.

Plots of land for clearing leases were mostly around ten or twelve acres, but if a tenant farmer was industrious and could prove his worth, he might be allowed as many acres as he could manage. If a tenant farmer had strong hard-working family members to help, then a clearing lease might be granted for plots as large as twenty or thirty acres.

Once cleared, the land was "let" on the halves principle - the landowner provided the land, seed, animals and tools and then took half the produce as a form of rent payment. This was the life of James Hukins for around ten years, beginning when we would have been around 52 years of age.

|

| Historical Electoral Rolls for Kiama, New South Wales 1855-1856 |

In 1854, at the ripe old age of 62, James then became a landowner himself. He bought 464 acres of land on Curramore Estate in Jamberoo. A year after that he sold 114 of these acres to each of his three sons - John, James and Adolphus - and kept 114 acres for himself. He named this patch of land 'Susan's Hill' which you may recall had been the name of a tract of land back in Devon, England where he had spent his childhood years.

James was to live out the remainder of his life at 'Susan's Hill'.

Sadly, in 1861 two of his sisters died, and then in 1862 his wife, Susannah, passed away. They had been married for 47 years and James was 69 years of age.

James himself passed away in 1871, at the age of 79.

|

| Death Notice - Empire, Friday 20 January 1871, page 1 |

The death notice posted in the Empire newspaper on the 20th of January stated:

"DEATHS. On Saturday, 14th January, at his residence Susan's Hill, Jamberoo, suddenly Mr. James Hukins sen., native of Woodchurch, Kent, England, aged 78 years."

Another newspaper article stated that James had suffered an apoplectic attack whilst walking on the verandah at his house and had collapsed and died.

"DEATHS. On Saturday, 14th January, at his residence Susan's Hill, Jamberoo, suddenly Mr. James Hukins sen., native of Woodchurch, Kent, England, aged 78 years."

|

| Armidale Express and New England General Advertiser Sat 28 Jan 1871 |

Another newspaper article stated that James had suffered an apoplectic attack whilst walking on the verandah at his house and had collapsed and died.

Special Note to any family members: If you have memories to add, photos or information to share, can I graciously ask that you do so. Please use the comments box below or email me. It may prove to be invaluable to the story and provide future generations with something to truly treasure.